Foiled in Congress, Trump Moves on His Own to Undermine Obamacare

Posted on October 12, 2017

The NY Times

By ROBERT PEAR and REED ABELSONOCT. 11, 2017

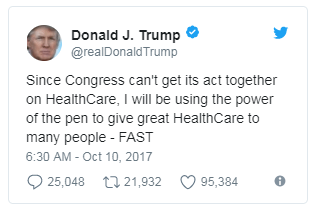

WASHINGTON — President Trump, after failing to repeal the Affordable Care Act in Congress, will act on his own to relax health care standards on small businesses that band together to buy health insurance and may take steps to allow the sale of other health plans that skirt the health law’s requirements.

The president plans to sign an executive order “to promote health care choice and competition” on Thursday at a White House event attended by small-business owners and others.

Although Mr. Trump has been telegraphing his intentions for more than a week, Democrats and some state regulators are now greeting the move with increasing alarm, calling it another attempt to undermine President Barack Obama’s signature health care law. They warn that by relaxing standards for so-called association health plans, Mr. Trump would create low-cost insurance options for the healthy, driving up costs for the sick and destabilizing insurance marketplaces created under the Affordable Care Act.

“It would have a very negative impact on the markets,” said Mike Kreidler, the insurance commissioner in Washington State. “Our state is a poster child of what can go wrong. Association health plans often shun the bad risks and stay with the good risks.”

They also worry that the Trump administration intends to loosen restrictions on short-term health insurance plans that do not satisfy requirements of the Affordable Care Act.

“By siphoning off healthy individuals, these junk plans could cannibalize the insurance exchanges,” said Topher Spiro, a vice president of the Center for American Progress, a liberal research and advocacy group. “For older, sicker people left behind in plans regulated under the Affordable Care Act, premiums could increase.”

But to business groups, the executive order offers an opportunity to bind their members together and sell large-group insurance policies that are cheap and attractive. Dirk Van Dongen, the president of the National Association of Wholesaler-Distributors, said that he was delighted with Mr. Trump’s initiative and that his group would seriously consider establishing an association health plan.

“Small to midsize businesses have very little leverage in the insurance market,” Mr. Van Dongen said. “Anything that allows them to amalgamate their purchasing power will be helpful.”

Large employer-sponsored health plans are generally subject to fewer federal insurance requirements than small group plans and coverage purchased by individuals and families on their own. They are generally not required to provide “essential health benefits,” such as emergency services, maternity and newborn care, mental health coverage and substance abuse treatment, although many do.

A decision by Obama appointees in 2011 discouraged the use of association health plans as a substitute for Affordable Care Act policies because officials feared they would be used to circumvent the law’s coverage mandates. The Obama administration said that coverage offered to dozens or hundreds of small businesses through a trade or professional association would not be treated as a single large employer health plan for the purpose of insurance regulation.

Instead, the Obama administration said, the government would look at the size of each business participating in the association, so that many small employers would still be subject to stringent federal rules.

The Trump administration, by contrast, wants to make it easier for small businesses to buy less expensive plans that do not comply with some requirements of the 2010 law.

Several states considered bills to treat health plans offered to small employers through a trade association as large-group coverage, exempt from federal rules that apply to small businesses. But the Obama administration blocked those efforts, saying they were pre-empted by the Affordable Care Act. Trump administration officials are reconsidering that interpretation, in view of the president’s vow to increase access to less expensive insurance.

Large-group plans are still subject to some requirements of the Affordable Care Act. They generally must cover children up to age 26 on their parents’ plans, cannot impose lifetime limits on covered benefits and cannot charge co-payments for preventive services like mammograms and colonoscopies.

But they are generally exempt from the requirements to provide a specified package of benefits and to cover a certain percentage of the cost of covered services.

The Trump administration is also looking for ways to ease restrictions on short-term health insurance plans that do not meet requirements of the Affordable Care Act. Under a rule issued last October by the Obama administration, the duration of such short-term plans, purchased by hundreds of thousands of people seeking inexpensive insurance, must be less than three months. The rules previously said “less than 12 months.”

The Obama administration said some insurers were abusing short-term plans and keeping healthier consumers out of the Affordable Care Act marketplaces. People are buying these short-term plans as their “primary form of health coverage,” and some insurers are pitching the products to healthier people, the Obama administration said.

But Trump administration officials say that with insurance premiums soaring in many states, consumers should be able to buy less comprehensive, less expensive coverage as an alternative to conventional plans. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce said short-term policies “serve an important purpose for consumers” who are between jobs.

That has some insurance experts worried. The influx of a set of plans exempt from the Affordable Care Act rules will essentially divide the market and make it increasingly unstable, said Rebecca Owen, a health research actuary with the Society of Actuaries.

People who want or need broad coverage could find it increasingly difficult to obtain an affordable policy, experts say. While the administration’s goal may be to give people a broader choice of plans, it could have the opposite effect on people who need or want the robust coverage available under the Affordable Care Act.

“The easier you make it not to buy comprehensive coverage, the harder you make it to buy comprehensive coverage,” said Katherine Hempstead, a health policy expert at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

As they waited for details of the executive order, health insurers still offering coverage in the online marketplaces created by the health care law were apprehensive.

Those insurers are most jittery about the possibility of a surge in short-term plans. Many of the large national insurers, like UnitedHealth Group, already offer these plans, and there would be little difficulty in their introducing more because of the executive order, analysts said.

“They can cobble these things together pretty easily,” said John Graves, a health policy expert at Vanderbilt University.

Individuals may already be attracted to short-term plans because of their low costs. These plans tend to limit benefits or offer policies only to people who do not have expensive medical conditions.

Short-term policies do not satisfy the coverage requirements of the Affordable Care Act, so consumers who buy them may be subject to tax penalties. But with the price of conventional insurance policies rising at double-digit rates, some people say they are willing to pay a penalty so they can buy a cheaper plan.

The introduction of new association plans could take much longer, according to insurers and other experts. The administration would need to work out the regulatory details, and groups would need to construct those plans.

But these plans pose some of the same risks, and industry experts warn that they have a history of leaving consumers with unpaid medical bills if they are not adequately regulated.

While association health plans can be well run, they “have had a spotty track record,” said Ms. Owen, the actuary. In the past, some plans failed because they did not have enough money to pay their customers’ medical bills, while some insurance companies were accused of misleading people about exactly what the plans would cover.